Solution page 13:

Gaming the System

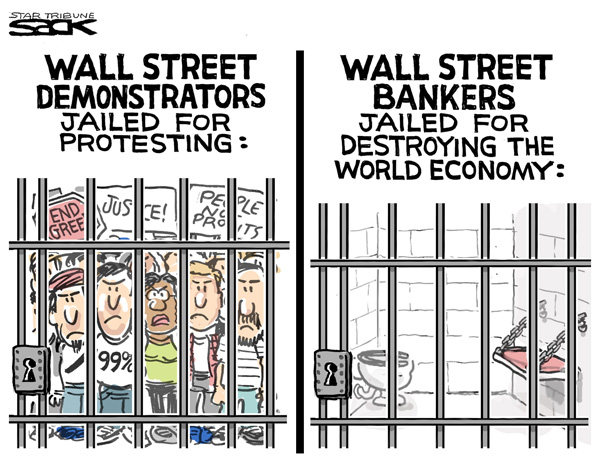

The current money system has long been noted for the many ways it can be "gamed", through criminal acts or legally. These crimes and abuses of the public good have been recognized by a substantial portion of the public now that income disparity and financial crime has been highlighted by the Crash of 2008, the Occupy Movement and similar uprisings worldwide.

How would the same criminally inclined persons pull a fast one in the Producer Credit system?

Several people have insisted that ANY system can be gamed. I have repeatedly invited them to submit their ideas of how the Producer Credit system could be manipulated to someone's unfair advantage, both within the rules and in violation of them. That invitation is still OPEN.

There has been only one rather obvious suggestion so far, from multiple sources:

The Issuer Spends Credits and then Closes Shop

In this scenario, the Issuer spends a lot of Producer Credits and then deliberately goes out of business and exits to parts unknown. In the current system, someone in the company could borrow money from a bank on behalf of the company and then abscond with the money in cash or by wiring it to an offshore bank account. Not so with Producer Credits.

Producer Credits aren't anonymous like cash in a vault that can be stolen or a Swiss bank account that can be emptied. Producer Credits can only be created by the Issuer, in most cases the company, spending them on something. This expenditure would show up in the records immediately. And, everything bought would be traceable the moment it was bought.

But, assuming the owner, the financial officer and bookkeeper all make their escape, the company closes and the Issuer's Producer Credits fall to zero value, the situation is exactly the same as covered under the page on Losses in general.

Fly-by-night operations spending fraudulent Producer Credits and then disappearing would rob whoever is holding their Credits just as with fake securities now. But how could that happen? It couldn't. It would take a record of dependable performance to establish that sort of volume of credit within the Producer Credit system. Only a desperate Issuer would throw that away.

Systemic Collapse?

Even if massive non-redemption of Producer Credits by an Issuer or several Issuers occurred, it could NOT bring the whole trading system crashing down, as threatened to happen with the current system, because each Issuer is its own "central bank", its own "lender of last resort", backed by its real productive resources and potential. Some Producer Credits would become worthless, among many still sound.

Other Possibilities

Counterfeiting

Preventing counterfeiting is a purely technical challenge that has to be met in the technical realm and will certainly be priority number one forever.

General Devaluation

General devaluation of Producer Credits could happen due to a tendency to overspend, but unlike devaluation of national currencies, it would not unavoidably affect a nation as a whole. There would be many Issuers worldwide and there would probably be many Producer Credits at par. Reliably at-par credits would tend to be held as savings, while devaluing ones would be spent quickly by some to minimize losses and bought by others as a speculative investment.

Given that devalued credit must be guaranteed by the Issuer to be redeemed at par, and over-valued Credits would create a shortage of product as well as hand the Issuer's profits to its customers, there would never be any advantage to an Issuer in deliberately devaluing or overvaluing its Credits.

To be perceived by the public as a devaluing credit that will not recover its value would be the kiss-of-death to an Issuer. The Issuer would be at the mercy of currency speculators or a fire-sale takeover. Remaining at par or very slightly above would always be the goal of a Issuer that wanted to stay in business.

Hostile Takeover

Let's imagine that Aggressor Corp. wants to destroy or takeover successful Competitor X using the Producer Credit system. How could that be done? The system automatically revalues Producer Credits in real time according to real transactions completed. Therefore, to affect the value of Competitor X's Producer Credits, real transactions must be completed.

If Aggressor Corp. buys up a huge amount of Competitor X Credits, it could withhold the Competitor X Credits as they near maturity, and drive up the value so that Competitor X loses all of its projected profits to its customers because they are redeeming Producer Credits at far in excess of par.

Competitor X is, therefore, also running out of stock before all the Competitor X Producer Credits issued against that stock are redeemed, and is thus at risk of default. Then, at the last minute, just before the Competitor X Credits expire, Aggressor Corp. demands redemption in a huge amount of product. Competitor X can't redeem its Credits on time and is now legally at the mercy of Aggressor Corp.

The Defense is Simple

To defend itself against such an attack, Competitor X would have to be alert to the over-valuation and spend immediately redeemable or short-term Competitor X Credits on the Producer Credits of other Issuers. This could be a pre-arrangement amongst defensive groups of Issuers to protect each other's Credit this way.

More immediately redeemable Competitor X Credits would bring the Competitor X Credits value back to par. If Aggressor Corp. now offers its excess Competitor X Credits on the market, their value will plummet well below par and be very close to expiring. Aggressor Corp. now has three choices:

1. take a total loss, or;

2. sell the Competitor X Credits to third parties, probably at a loss;

3. accept payment from Competitor X in the other Producer Credits Competitor X acquired or;

4. insist on redeeming the Competitor X Credits for Competitor X product.

In the first case, the Aggressor Corp. takes a loss in order to push Competitor X Credits below par and try to start a run on the company's Credits. However, Competitor X has other Producer Credits, presumably at par, with which Competitor X buys up its excess Credits, nullifying the attack. Not only is Aggressor Corp. foiled, but Aggressor Corp.'s loss is Competitor X's profit!

In the second and third cases, Aggressor Corp.'s attack is turned back and nullified.

In the fourth case, Competitor X is capable of paying for the required production with the Credits of the other Producers it bought to defend itself. Buying the necessary time might require a decision by a court. If this system were the prevailing system, the legal procedures for this situation would be well mapped out and probably require rigidly arbitrated settlements to save court costs. In the case of obvious aggression, why would the rules favour the aggressor?

Given these outcomes, such aggression via currency manipulation does not seem promising.

Self-destruction more Credible

If Aggressor Corp. did succeed in creating a run on Competitor X 's Credits

it could bring down the company. But, as described in Money as Debt III, the more likely scenario for creating a run might be the employees of an Issuer losing confidence in their own employer and "dumping" their wages in such volume as to devalue their own pay and create a self-fulfilling prophecy, further loss of confidence, further dumping by the public and further devaluation. In the case of a serious loss of value, Competitor X Credits would depend on the assessments of currency speculators to survive.

Currency Speculators

Under normal conditions, currency speculation would automatically stabilize any Producer Credit's value back to par. As soon as a reliable Credit dropped below par for any reason, speculators would buy it, pushing it back up to par or above. As soon as it reached its estimated top and before Issuer remediation kicked in (as described in Defense above), the speculators would sell the Credits again, driving the value back down towards par or below. Repeat.

In the case of a loss of reputation, discerning whether a company's real demand will survive an attack on its reputation would be the role of the currency speculators. In their own best interest, currency speculators would have to exercise due diligence and sound evaluation of credit risk. Such due diligence would be a public service rendered for profit by private interests at their own risk, not a government bureaucracy.

The Section of Money as Debt III on Devaluation & Speculation

Brokers and Speculators

This is where the scamming could be done and strict enforcement of three simple rules would be required.

The rules of this system must stipulate that brokers get paid their fees by both sides of each transaction, in the exact same mix of Producer Credits they transact for their clients.

These are clear and common sense rules that would keep brokers honest and effectively provide a functional replacement for credit rating agencies.

The big question that would repeatedly come up would be... should Producer Credit brokerages be allowed to speculate in Producer Credits for their own profit? Given that brokers could influence the swings in value, NO.

Potential conflict-of-interest could only be avoided if brokerages and speculators were strictly separated. In addition, this would make the speculators' assessment of the credit risk of any Issuer independent of the brokerages' assessments, an additional pressure to keep Issuers and brokerages honest and factual.

back /